BLUE SILENCE

Proposal for a feature film, based on a true story

© David Lowe, September 1998

BACKGROUND

The sinking of the HMAS Armidale is a story of courage, sacrifice and survival. It's also the story of a tragic mistake, and the cover-up that followed. As a piece of history, it's clearly a story which needed to be told. As a piece of drama for the big screen, the history presents some problems.

THE INQUIRY

Firstly, I don't believe there is the material here for a courtroom drama. Unlike Breaker Morant and A Few Good Men, this is not a court martial story. To make it into that type of film would mean stretching the facts of the history beyond breaking point. There are no lives at stake in the inquiry, no pending executions, no innocent people to be saved. The damage, to a large extent, has already been done. What is at stake at this point are people's reputations, the memory of the dead, and the truth. Although these things are extremely important, they are somewhat intangible when seen in the context of the inquiry alone.

SURVIVAL AT SEA

Another approach to the script might be a straight survival-at-sea epic. There is no shortage of extraordinary historical material to draw from, and there are also clear life and death stakes. There is conflict between the survivors and the Japanese attackers, between men and nature, and even between the survivors themselves. The drawbacks of this approach include the separation of story strands as the survivors break into three separate parties, the loss of the intrigue/cover-up story, and the high cost of a film set entirely in the open sea, with lots of expensive period action props, and nowhere very dramatic to cut away to.

ANOTHER APPROACH

Rather than choosing either of these options, it seems to me that the best approach in terms of drama might be to create a new type of film, a survival story/cover-up/romance. Instead of forming the basis for the whole script, the official inquiry could serve as a springboard for a deeper investigation of what happened, powered by a personal, emotion-driven quest.

NEW CHARACTERS

I propose to create three fictional characters as a way of exploring the facts of the story:

Lucy Holmes. A young officer in the Womens' Royal Australian Naval Service, stationed in Darwin, under the command of Commodore Pope. Lucy is appointed as shorthand writer to the sensitive naval inquiry into the Armidale sinking. Unknown to Pope, who served in World War One with her father, and is like an uncle to her, Lucy has a secret romantic interest in one of the men who went out on the Armidale and didn't come home. Lucy risks her own career, her relationship with her family, and eventually also her life, to get to the heart of the Armidale incident and its aftermath.

Jack Poole. A young AIF corporal. One of the survivors of the Armidale sinking. A bit of a larrikin and a rebel, Jack wants people to know the truth of what happened, and why it happened, but the Navy is determined to silence him for reasons of its own. Jack and Lucy meet when he testifies at the inquiry. As it turns out, Jack is also the one who will pass on to Lucy the extraordinary story of the fate of her lover, one of the heroes of the Armidale.

Lloyd Downie. A middle-aged, washed-up Darwin journalist who works as a stringer for the big southern papers. Lucy must convince Downie that there is more to the Armidale story than meets the eye, but Downie is like the audience - cynical, and difficult to convince. Lucy's dangerous private investigation into the tragedy will only be worthwhile if she can persuade Downie to risk the wrath of the military censors, defy the cover-up, and run the story.

BLUE SILENCE

My proposed title refers to the fate of the men who went down with the Armidale, particularly the hero of the day, Teddy Sheean, and also to the lack of acknowledgement from the Navy of that heroism, as well as that of the other survivors. In the course of her investigation, Lucy strikes something of a wall of silence and deception from the Naval powers that be. Their symbolic colour is also, of course, blue.

WHY USE A WOMAN CHARACTER TO TELL A MENS' STORY?

The survival story, it seems to me, is vitally important to this narrative, but does not justify an entire film on its own. The inquiry story is fascinating, but lacks the substance to form the basis of its own film. Both stories lack a clear dramatic through-line, and although there is much tragedy and drama to be found, there is not the necessary sense of contemporary relevance, as it stands, to draw a young international audience of both sexes in the late 1990s.

What can be readily drawn from the history is a strong story of young men in trouble as a result of their elders' mistakes and inability to move with the times. The approach I am suggesting brings the addition of a love story - as well as emphasising the intrigue and mismanagement-in-high-places angle - via a fictional insider character who becomes an outsider through necessity. These sorts of stories are universal, and more relevant now than ever, as can be seen from the success of modern myths like the X Files and Titanic.

My proposed script will weave the survival, inquiry and cover-up elements together via the device of a personal investigation into the tragedy by a questing, passionate young woman. At stake will be the reputations and memory of the dead, the future of the living survivors, the fate of the three fictional characters, and the truth.

ARCS

Lucy's arc through the story parallels the journey of the film itself. Starting within the safe but emotionally barren naval command structure, far from the front line, and as a part of the machinery of the cover-up, Lucy's investigation leads her through the baptism of fire of the survival story (revealed via flashback), and ultimately to a position of great physical and psychological danger, on the streets of Darwin, caught between the authorities and the brutal force of a Japanese attack.

Emotionally, the journey is from cold to hot, from suppressed to surface emotions, from internal to external violence. Lucy goes from being guarded to vulnerable, from being part of an organisation to being an individual, from being a cold recorder of facts to a passionate and grieving lover; questing for and finding a painful but important truth. In the process, she starts a chain of events which will eventually lead, fifty years later, to the actions of the men of the Armidale finally being remembered, and accorded their rightful place in history.

BUDGET

In terms of budget considerations, the proposed approach allows as much or as little expensive action to be shown as desired. The balance between flashback and retelling is flexible, because the drama of the story is not all in the past (the survival story), or the present (Lucy's story), but lies in a combination of both.

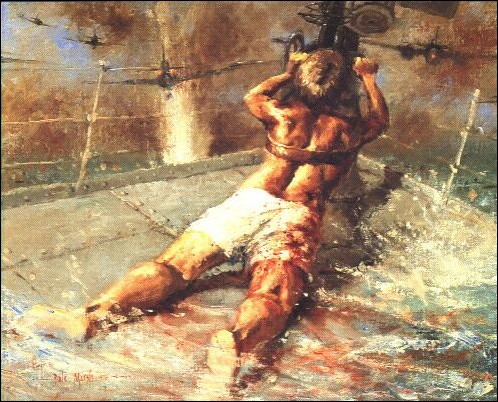

I do think that it would be a great pity to under-budget the story to a point where the audience saw nothing of the survival-at-sea story, and although my approach avoids showing much of the air-sea conflict with the Japanese (minimising the need for period military hardware), I think it's absolutely vital that the audience see, in graphic detail, a re-creation of the Teddy Sheean Oerlikon incident, in which only a small part of the ship was actually above water (i.e. that's all that would need to be built). This amazingly heroic moment, which will be held back until late in the drama, is the emotional core of the story for me, and should be a high point of the film.

(Note: There are some exciting new options for shooting open water scenes on a restricted budget including digital/miniature combination techniques and the new Melbourne horizon tank, recently used to shoot Moby Dick).

THREE WORLDS

In a sense, there are three dramatic zones within the world of the proposed film:

Darwin in wartime. Not quite a city, not quite a town. The northern, tropical frontier of a southern continent. At constant risk of invasion from the Japanese, and already invaded by waves of American troops. The victim of ongoing, destructive bombing attacks from the north. A chaotic, cosmopolitan place, awash with black market liquor and rumours.

The courtroom and naval base. An alien, man-made environment, guarded from the outside world with guns, barbed wire and codes. An artificially cooled, clinical place where rules and regulations are tangible, procedure is everything, and emotions are irrelevant. Rigid, old-fashioned structures of command have been known to replace and overwhelm true leadership here. Cowardice, passing the buck, and incompetency is paid for in human lives. The most dangerous thing you can do is to question the status quo.

The sea. Hostile and unforgiving. After a few days without rescue, and without water, a hallucinatory place; otherworldly, strange, awful, magical. Full of terrors, below and above the water. Sharks, sea snakes, bombers, machine guns from the sky, hunger, thirst, waves and sun. A million miles from the world of those in charge, this is the place where heroes are made, and only those with ingenuity, bravery and luck survive.

A POSSIBLE STRUCTURAL APPROACH

What follows is an early structural approach to the proposed script. Act 1 (approximately the first thirty minutes) is outlined in some detail over the next four pages. The remainder of the film is sketched in less detail after that.

In broad terms, the setup of the story (Act 1) is concerned with the official inquiry and introduces the main characters. The development act (2) deals with the survival story and cover-up, as revealed by Lucy's unofficial inquiry. The resolution (Act 3) deals with the human costs of the cover-up, and answers the question of why Lucy has been on this quest, as well as revealing the heroism of Teddy Sheean...

Sydney, December 1942. Although it is wartime, Christmas decorations flap in the city streets as busy Sydney-siders shop for presents. On Pitt Street, in the heart of the city, respectable people move aside to avoid three ragged men who look like desperate escaped criminals. Dressed in tattered army cast-offs, wounded and half starved, with their hair matted with blood and oil, the men enter the foyer of a beautifully appointed city office building. They enter the lift, resting on each other for support. Horrified office-workers shrink away from them, covering their noses to avoid the smell of festering wounds.

The men leave the lift and approach a well-to-do secretary. One of the men speaks, with difficulty: 'Is Mr Caro in, please?' The secretary retreats and emerges with a respectable-looking older gentleman in a suit. 'What's the meaning of this?' he says. 'Who the devil are you?' Again, the leader of the ragged men has difficulty speaking. 'It's me, grandpa. Don't you recognise me?' The older man looks hard into his face. Suddenly realisation dawns. 'Good God, is that you, Russell?' The younger man collapses into his arms. Horror turns to concern as Caro recognises his grandson. 'What have they done to you?' he asks. 'What's happened?'

The titles sequence ends with the wheeling, stylised perspective of the POV of a sinking ship under machine gun fire and torpedo attack. Smoke, noise and sky is suddenly replaced by muffled screams, thumping bullets, and blue water. The silence becomes more profound as the water becomes deeper, and blue turns to black. Title: 'Blue Silence'.

Darwin, one week earlier. HMAS Melville, a naval base in the far north of Australia. A junior officer from the Womens' Royal Australian Naval Service, Lucy Holmes, is ordered to the office of the Naval-Officer in-Charge of the base, Commodore Cuthbert Pope. An attractive young woman, Lucy isn't particularly tall, but her military bearing and uniform are impressive as she moves down the corridor, determined not to let her guard down in this male-dominated environment. Only her eyes betray any hint of vulnerability.

Pope is tall, severe-looking, in his mid-50s. He softens when he sees Lucy. He explains that there is to be an inquiry into what he describes as an 'unfortunate incident'; the recent sinking of a naval corvette off the coast of Timor, the HMAS Armidale. He needs a shorthand writer to cover the inquiry, but is quick to emphasise that he isn't asking Lucy to do this secretarial job because she's a woman, or because there's no one else who has the skills; it's because the inquiry is 'sensitive'. He needs someone he can trust. Lucy, it seems, has risen through the ranks quickly, and has a bright prospective future in the WRANS as one of its leading young women officers (her father served with Pope in World War One).

There must be no leaks from the inquiry, Pope explains, as the results could affect the lives of men still in the field. In his fatherly manner, he asks Lucy if she understands why he has asked her to do this job. Lucy says she understands perfectly, and adds that she is happy to do whatever is asked of her. 'Good girl,' says Pope. 'With that attitude you'll go far.'

The inquiry opens in the cool, clinical atmosphere of a room inside HMAS Melville. The violence and chaos of war seems far removed from this ordered place, where fans keep things cool, and everything happens according to procedures described in the Navy's 'Bible', the King's Regulations and Admiralty Instructions.

As ordered by Commodore Pope, who comes and goes from the inquiry between other duties, the investigation is led by two senior RAN officers, Commanders Tozer and Donovan, along with one of Pope's junior officers, Lieutenant-Commander Malley.

The inquiry hears testimony from a number of survivors of the Armidale sinking, all of whom are wounded, some seriously. The approach of Tozer and Donovan is businesslike, and very formal, with little regard for the fragile physical and psychological state of many of the witnesses.

Lucy listens intently, and takes down everything that is said in shorthand. She sits beside Malley, a serious man in his late 30s with a weight of knowledge on his conscience. As the story continues, Malley becomes a source of inside and supporting information for Lucy. He also offers an alternate perspective on his superior officer, Commodore Pope, who has been something of a father figure for Lucy during her time in Darwin.

First on the stand is the captain of the Armidale, Lieutenant-Commander David Richards, a Navy reservist. Richards, a respected, courteous officer in his late 40s, seems to be under some nervous strain, but answers the questions asked of him efficiently, with a somewhat apologetic manner. The questions, from a prepared list, are fairly dispassionate and matter-of-fact; they relate to the time and location of the sinking, the nature of the attack, and whether confidential codebooks and packages went down with the ship.

The picture that emerges is of a small, hopelessly outgunned and under-defended craft, sunk by a determined and ruthless enemy using Zero fighters and torpedo bombers, and without air support when it was most needed. No questions are asked about the aftermath of the sinking, and Richards is not invited to elaborate on individual acts of heroism, the reasons for the mission, or its cost in human terms, despite his own obvious desire to say more.

Next to appear is Lieutenant William George Whitting, a younger man who appears to be paralysed from the waist down from wounds sustained during the attack, and is in a wheel chair. The questions cover much of the same ground, and Whitting's answers corroborate Richards' version of events, but Whitting's answers are more graphic, and are supported by moments of vivid flashback to the fear and confusion of the attack, particularly as Whitting is requested to draw a sketch of the attack. The sketch shows fighters and bombers approaching from every angle, with crosses marking the position of hits by bombs and torpedoes.

Whitting's evidence is followed by quick cuts between the evidence of three other survivors, a mechanic and two ordinary seamen, whose less educated, more emotive language provides a terrifying view of the attack from the perspective of the men below decks, fighting through rushing water, blood, and pieces of bodies to try to free whatever safety equipment they could before the ship went down. Again, the spoken evidence of the courtroom is supported by short, sharp, intense flashbacks as the men remember their horrific experiences.

Throughout this testimony, Lucy is the face of professionalism, betraying no emotion. When an adjournment is called however, she goes to the Ladies Room and weeps, holding a locket which she wears around her neck, apparently overcome by what she has heard. Returning to the courtroom, Lucy witnesses a confrontation in a side corridor between Pope and another man, also in uniform, who appears to be his junior. Pope is furious about a report this man has written, and what he describes as 'indefensible insubordination'. The other man is equally furious, if more contained, and seems to be highly critical of Pope's handling of the whole Armidale affair. The men don't see Lucy, who is careful to stay out of sight. The men break off their argument when they are disturbed by Tozer.

The inquiry reconvenes with the testimony of one of the members of the board of inquiry, Lieutenant-Commander Malley, (the man who has been sitting beside Lucy until now). Malley's evidence concerns the signals that passed between the Armidale and Darwin leading up to the sinking. The signals illustrate a series of attacks, over a period of hours, and contain numerous requests for fighter support, none of which resulted in such support being given (aircraft were occupied with another, unspecified operation at the time). Malley explains that the sudden cessation of radio communication from the Armidale was thought at first to represent compliance with an order for radio silence, due to the suspected presence of Japanese cruisers in the area. It seems command was not aware that there was anything wrong until the next day, when the Armidale failed to report.

During Malley's testimony, the man who was arguing with Pope in the corridor quietly enters the room and sits down to watch proceedings. When Malley returns to his seat, Lucy asks him who the man is. He explains that it's Lieutenant-Commander Sullivan, the captain of HMAS Castlemaine, another ship involved in the Armidale operation.

The final witness of the day is a young AIF man, Corporal Jack Poole, called to the stand to explain why no distress signal was sent from the Armidale before she went down. While Poole is making his way to the stand, with difficulty, on crutches, Tozer asks Malley why a naval man couldn't have been called to explain this matter. Malley explains that all the other seamen who were in that part of the ship are either too badly injured, or dead.

Poole is a bit of a larrikin. As an infantry man he has less respect than the other witnesses for the command structure and processes of the navy. His perspective is that of an outsider whose fate was tied up with that of the navy boys by misfortune. Tozer and Donovan become increasingly irritated with Poole as his testimony goes on. Unlike previous witnesses, he refuses to restrict himself to the questions, and constantly provides unwanted elaboration.

Poole explains that he was assigned to the Armidale mission as a gunner, but that the ship was not properly armed to deal with air attack. He describes being near the mess area where a large group of soldiers carried by the Armidale were killed simultaneously by the same torpedo - a piece of shrapnel from the blast ripped through the wall and destroyed the radio area, killing the radio operators and one of the officers as well.

Having heard Poole's explanation of why no distress signal was sent, Tozer and Donovan move on to the form questions asked of every witness. When did the attack take place? What form did it come in? How long did the ship take to sink? Poole answers, but is obviously irritated with this line of questioning. 'Don't you know all this already?' he asks.

Suddenly Pope returns to the room. He rebuffs Poole and says that the same questions need to be asked of each man, so as to be clear about what happened and uncover the truth. Pope thanks the AIF man for his assistance, and says he is dismissed.

Poole is confused, and angry. He points out that none of the important questions have been asked. Why was the Armidale sent back into danger alone without adequate air cover? Why is the sinking being hushed up? Why did he wake up in hospital with an armed guard watching over him? Pope firmly reminds Poole that he has been dismissed.

But Poole will not be silenced. He says the inquiry is a sham, a cover-up. He continues railing as military police move in on him. 'Why are the survivors being treated like criminals?' he asks. 'Why is their bravery going unrecognised? What happened to the men on the raft? Why didn't Teddy Sheean get a VC?!' The MPs grab Poole and drag him away. Outside the inquiry room, Poole is finally silenced with a pistol butt in the stomach. The military police carry him off down the corridor.

Inside the inquiry room, everyone is shocked at what has happened. Pope tells Lucy to withdraw Poole's testimony from the record. He says he will speak to Poole's army superiors to ensure the man is punished for his behaviour. Suddenly Pope notices Lieutenant-Commander Sullivan sitting at the back of the room, watching intently. 'Who let him in?' he demands of the guards. 'This is a closed inquiry'.

The MPs usher Sullivan from the room. 'You can't silence everyone,' says Sullivan. 'It's true. The wrong questions have been asked'. Pope says that if Sullivan has anything to say, he can say it in his report, and he'd better back it up with hard evidence. 'One more word from you, and I'll charge you with insubordination,' he thunders. 'This inquiry is closed'.

Lucy is troubled by what she has seen and heard. Later that day, she delivers her typed-up account of proceedings to Pope's office. He tells her not to be worried by what happened in the inquiry. 'War does strange things to men,' he says. 'You'll learn that if you go on in this business'. Lucy smiles, and turns to go, but she's not convinced. Malley catches her eye as she leaves Pope's office. He can tell that something is troubling her.

That night, out of uniform, Lucy visits a local journalist, Lloyd Downie, who works as a stringer for the southern papers. Downie is cynical, washed-up and middle-aged, with few passions remaining in his life other than alcohol. Lucy refuses to tell Downie who she is, but says there is an untold story behind the Armidale sinking that needs to be told.

Downie is not convinced, asks her for details. Lucy says she doesn't have any, the story needs to be investigated, but she is sure that there's a story there to be found. Downie responds that there are a million stories in a war, and almost as many that the military won't allow to be told. He explains that all news reports emanating from Darwin have to go through a tight censorship net, and even then the communication lines to the south are cut half the time. According to Downie, even the biggest stories have to battle to reach the front pages. Because of the censors, he says, hardly anyone down south even knows about the ongoing Japanese bombing attacks on Darwin that have left hundreds dead. As a journalist, it's hardly worth trying.

Lucy is incredulous. She tells Downie it's his duty to let the public know what's happening. What about the dead men's relatives? Downie says that if she knows there's more to the Armidale story than meets the eye, then she must be inside the navy herself, and if that's the case then she's far better equipped to uncover the story than he is. 'If you find any concrete evidence,' he says, 'then come back to me, and bring some military issue Scotch with you.'

ACT 2

Aware that no one is going to get to the truth if she doesn't, Lucy begins her own tentative investigation into the sinking of the Armidale. In between running errands for Pope, Lucy asks questions of the naval officers, including those who testified at the inquiry, but no one, not even Sullivan, will break the sanctity of the command structure by talking to a junior woman officer about the matter. Malley, it seems, would like to help, but is close to Pope and too fearful to give Lucy any useful information - yet. She tries to speak to the rebellious AIF man, Jack Poole, but he's confined to barracks. One of his guards, though, is sympathetic, and allows some information to flow between Jack and Lucy.

When he becomes aware that Lucy is within the command structure of the navy, and perhaps represents the only way to get the story of what really happened to the public, Jack smuggles out contacts for Lucy to speak to - other survivors. Covert discussions with damaged, frightened men in barracks, pubs and hospital wards spark flashbacks to the survival story, the cover-up, and the extraordinary ill-treatment of the men on their return.

The reason for the mission, it seems, was to relieve a team of Australian and Dutch-led native soldiers fighting a desperate rearguard action against the Japanese on the island of Timor. An initial rescue mission using a bigger ship ended in disaster, leading to the tiny corvettes being called in, but a combination of bad luck and mistakes from above led to the botch of a crucial rendezvous. With wounded refugees on one ship, the Castlemaine, and reinforcement troops on another, the Armidale, Pope decided that sending the second ship back to Timor for another attempt represented a 'justifiable war risk'. On the understanding that there would be air support, and in spite of the objections of the Castlemaine's captain, Sullivan, the Armidale ventured back into hostile waters. But the Japanese tracked the ship, and were aware of its every move. When the inevitable attack came, there was no air support. Despite a desperate defense from the officers and men on board, over several hours, eventually a concerted, well-organised Japanese attack led to the sinking of the Armidale.

The stories of the men who were there, supported by flashback, give Lucy a picture of what happened after the sinking. When the Japanese machine-gunners ran out of bullets and flew away, a new battle began - a battle to survive. With almost all the food and water lost, surrounded by the dead and dying, oil welling up from the sunken ship and sharks and venomous sea snakes all around, the survivors found themselves in water that was almost two miles deep, and hundreds of miles from safety. There was also immediate tension between the Dutch officers and their armed, native troops and the unarmed Australians. Half submerged rafts and pieces of wood now became vital territory, to be fought for or conceded.

Emotions and truths begin to well up to the surface, but Lucy's own story and emotions are still under wraps. We are led to believe her personal interest is probably in a young officer who was left on one of the rafts and has not been found - the people she's talking to assume that Lucy, an officer, would never be involved with an ordinary seaman.

From the men who were there, she hears the stories of Lieutenant Lloyd Palmer, whose tenacity and leadership got the whaler to safety, Captain Richards, who played a similar role in the motorboat, and the many equally extraordinary acts of bravery, endurance and ingenuity performed by the ordinary sea and infantrymen.

Gradually a story of violence and heroism emerges. As she fits the pieces of the survival story together, there is also the ongoing intrigue plot to which Lucy is a party in Naval Command.

Memos and reports fly through Commodore Pope's office as the Board of Inquiry prepares to publish its findings. Pope is furious at the inclusion of Sullivan's request for a full inquiry into the operation that led to the sinking, and Lucy is forced to edit out questions about Pope's role in the sinking from the report that goes to the Prime Minister.

There is little that anyone can do. As Malley points out to Lucy, there was never much prospect of the inquiry delivering a negative finding against the Commodore. After all, Pope set it up, and those who sat on the inquiry were his juniors.

It becomes obvious to Lucy that what really caused the sinking of Armidale was Pope's underestimation of modern air power. Having learned his trade in an age where only a ship could sink another ship, and air forces were largely irrelevant, Pope is mentally unprepared for a war that led to catastrophes such as Pearl Harbour and the Blitz. Although he is a brave and honourable man, Pope's dismissal of air attacks as 'ordinary, routine, secondary warfare' led ultimately to the destruction of the Armidale, and 100 deaths. This is the awful truth which is now being covered up, both from the Australian public and Allied command.

Pope's dangerously old-fashioned attitudes to air power, and sacrificial notions of bravery, are dramatically demonstrated when there is an air raid on Darwin. While everyone else runs for the air shelter, and the windows are blown out by falling bombs, Pope holds his ground, and rants at the others for their cowardice, completely unable to see how crazy he looks.

Again, Lucy goes to the journalist, Downie. With her revelations (and a bottle of Scotch) she hooks him, but Downie still needs more before he can get his editors to accept the story and risk the wrath of the military establishment - something extraordinary, something personal, something that will stir a war-weary nation from its apathy. Lucy says he is being unreasonable, what more does he need? But there is a sense that she is also unsatisfied. She needs to talk to Jack Poole, ask him about something he said in the inquiry, but Jack is now in solitary confinement for his insubordination, and unavailable. She's on her own.

Pope tells Lucy to go home for Christmas, and offers her early Christmas leave. She becomes aware of the immense strain Pope is under as he sees her to the RAAF base. It is clear to Lucy that he is the one that needs early leave, not her, but Pope will not listen to reason. He tells her he is afraid that someone is leaking information about the Armidale matter - he cannot leave. Despite the increasing risk, Lucy cannot leave either. Using a clever subterfuge, she tricks Pope into thinking she has got on the plane, but actually sneaks out of the airport, and back into the city, to finish her investigation.

In this act, the theme of betrayal is developed (the betrayal of the men by Pope, the betrayal of Pope by Lucy), as each branch of the survival story, and its aftermath, is explored via the testimony of a different survivor. Although Lucy can get no information from those senior to her now that she is operating covertly, the navy command structure means that the junior men are duty-bound to answer her questions, not knowing that her investigation has not been sanctioned from above.

Lucy discovers that the survivors of the sinking were split into three parties; those who left to get help in the ship's crippled motorboat (rescued after six days at sea), those who managed to raise and patch the ship's sunken whaleboat, in spite of extraordinary odds (rescued after eight days), and those who stayed behind on the rafts; a mixture of Australians, Dutch and native troops. This final group of men came tantalisingly close to rescue by sea plane, but then mysteriously disappeared (presumed drowned, or captured by the Japanese).

From the motorboat group, Lucy speaks to Motor Mechanic Les Higgins and Leading Signalman Arthur Lansbury (both of whom also appeared at the official inquiry). From the whaler she finds Wireman Bill Lamshed and Stoker Ray Raymond. The men's stories, and flashbacks, illuminate a nightmare world in which only those who worked together survived, where rain was a miracle, where skills brought by the survivors from their previous existences saved lives, and where the average age of the men was only nineteen.

Lieutenant-Commander Malley risks his own career by helping Lucy in her pursuit of the truth, feeding her necessary information from inside Pope's office now that she is in hiding. Malley is attracted to Lucy, but he becomes aware that she is in love with someone else, one of the Armidale men. Although he doesn't know who the man is, whether he's confirmed dead or missing, Malley is the first to suspect that Lucy's lover might not be an officer, but an ordinary seaman. As an officer himself, well aware of the unwritten rule of the services, Malley understands why Lucy must continue to keep the romance secret, for whoever this man is, or was, he was her junior, both in age and rank, and the relationship is impossible.

Pope meanwhile becomes increasingly concerned about the security leak from the base. Intelligence confirms that someone has been talking to the press. He doesn't suspect Lucy as yet, but is worried when her father says she hasn't come home for Christmas...

ACT 3

Via Malley, who is sympathetic to their cause, Lucy is contacted by another group of survivors, men who were considered well enough to travel and were sent south before they could speak to the inquiry. Silenced by the Navy under threat of court martial, and forbidden to speak to anyone about the Armidale incident, including their families, they secretly contact Lucy in the hope of having their stories told. Amongst them are Russell Caro and the other men seen at the start of the film, in the Pitt Street scene.

Again supported by re-enactment, Lucy comes face to face with the human results of Pope's cover-up. Instead of the heroes of the Armidale receiving a tickertape parade, they were sent south by troop train and ship without even being given new clothes or proper medical care. She discovers that one survivor, Ordinary Seaman Ted Morley, was forced to travel for days by bumpy road, train, transport plane and ship with a horribly shattered, infected jaw; an injury sustained weeks earlier during the Japanese attack on the Armidale.

Pope's intelligence people trace the source of the leak to Malley, who flees from the naval base moments before he is arrested, leaving a pile of official photographs of the dead sailors behind on Pope's desk to remind him of the human cost of his mistake. When Pope discovers that Lucy is involved, and is still in Darwin, his concern for her safety turns to rage. He organises a detachment of military police to hunt her and Malley down.

Under pressure from Malley, who is also now in hiding, Lucy finally admits her personal stake in the Armidale story. There was a man, they were having a secret affair. He was an Ordinary Seaman from Tasmania. His name was Teddy Sheean, and he was only eighteen. They met when both were stationed in Townsville. It was love at first sight. Lucy's family heard of the affair, though they didn't know the identity of the man involved. Her father, horrified at the possibility of disgrace, had her moved to Darwin, under the wing of his old war buddy Pope. Unknown to them, Teddy Sheean was also moved to Darwin shortly before his fateful mission to Timor on the Armidale.

Flashback to Lucy and Sheean out of uniform on their final day in Darwin, happy and together. He is very young, a handsome boy. They are very much in love. They have their photo taken together by a Chinese photographer, smiling and embracing.

Back in the present, Malley is moved. Lucy explains that for all the interviews, for all the questions, and stories, she still doesn't know what happened to Teddy. She explains that she couldn't ask the men directly about him for fear of the shame - her father, to whom she was like a son, would never forgive her for throwing her career away for love - and that's what would happen if her superiors found out about the relationship.

Lucy explains that she doesn't want to end up like her mother, trapped in a loveless marriage, or like her father, a man who is actually married to his career. But now Sheean is among the missing, or dead. Only Jack Poole, it seems, knows more, and he cannot be contacted. Flashback to Jack's outburst at the trial: 'Why didn't Teddy Sheean get a VC?!'

Malley, together with one of the survivors, an AIF man who is grateful to Lucy for her promise to tell his story, manages to find out where Jack Poole is stationed. It seems he has been transferred to another base in Darwin. Having recovered from his injuries, he is about to be shipped back to the front.

Lucy is due to meet Downie again that night. She has to get the full story now, or never. Avoiding the military police, she manages to catch up with Jack moments before he is shipped out. They're practically on the gang plank, and there is little time, with Jack due to leave at any moment. Supported by generous, graphic flashback, Poole tells the story of Teddy Sheean's last moments...

Strafed by machine gunners and torpedo bombers, the ship is going down. Ordinary Seaman Teddy Sheean sees the plight of the men in the water and still in the ship, and realises there will be a massacre if nobody does anything.

Acting with great courage, Teddy moves from his position of relative safety, and the possibility of rescue, to struggle, wounded, up the steeply sloping deck of the crippled ship. Strapping himself into the Oerlikon gun on the bow, he cocks the gun, and begins fighting back. Unseen by many of the men, and lost in the chaos of the moment, he manages to hit two Japanese fighters, downing one, before being mortally wounded in the back and legs by machine gun fire. Still Sheean keeps fighting, water lapping at his feet as he swings a stream of shells through the air, forcing the Japanese fighters to turn away, and hitting another plane.

As the ship sinks, he keeps firing, dragging his useless legs behind him, until he is dragged beneath the waves, still strapped into the gun, firing to the end.

Jack points out that this was not an act of empty heroism. Sheean's sacrifice created just enough time for rafts and floats to be launched, and for depth charges to be disarmed before they could kill the men in the water. By giving up his own life, many others were saved. One of those lives was Jack's: the Zero shot down by Sheean was just beginning a strafing run straight through Jack's group of survivors, and he would have been first in line to be hit.

As he says good bye to Lucy, and walks up the gangplank to his destiny, Jack reveals that he knew of the relationship between Sheean and Lucy all along - the younger man had confided in him. 'He adored you,' Jack tells Lucy.

Back in town, Lucy has just finished telling the story to the journalist, Downie, as the air raid sirens sound. 'Will you get the story out?' she asks through her tears. Downie, moved, promises that he will - Sheean and the other men of the Armidale will not be forgotten. He says he will move heaven and earth to get the real story past the censors and out to the people. If necessary, he will carry the copy south himself.

Downie and Lucy are in a café. Outside, heedless of the air raid, Pope and his military police are hunting Lucy down. Screaming people run for shelter as they hear the bombers approach. Lucy and Downie go to the entrance of the café. Pope and a jeep-load of military police are in the distance, approaching from a street on the right. Pope sees them.

'Quick!' yells Lucy. Avoiding Pope, Lucy and Downie run in the opposite direction, taking the street on the left. Suddenly a bomb falls right in front of them. There is a huge explosion. As the bombers fly past, Pope turns the corner and runs towards the crater. He finds Downie, dead.

Some distance away lies Lucy. Her breath is very short, her face pale and streaked with blood. She holds something tightly clutched in her hand. Through ragged breaths, she tries to say something to Pope. He leans over her, his anger forgotten now. As she dies, she whispers a word: 'Remember...'

The military police try to drag Pope to safety, but he waves them away as Lucy's hand falls open, revealing a locket. Full of mixed emotions, Pope opens the locket. Inside is a photograph. It's Teddy and Lucy, young and beautiful. Alive. He recognises Sheean from the photos Malley left on his desk. At last, Pope understands why Lucy betrayed him.

POSTSCRIPT

Corporal Jack Poole was lost in action.

Corporal Jack Poole was lost in action. After the sinking of HMAS Armidale, Lieutenant-Commander David Richards was never given another major command.

After the sinking of HMAS Armidale, Lieutenant-Commander David Richards was never given another major command. In failing health, Commodore Cuthbert Pope was promoted and became Naval-Officer-in-Charge, Fremantle.

In failing health, Commodore Cuthbert Pope was promoted and became Naval-Officer-in-Charge, Fremantle. Teddy Sheean was never awarded the Victoria Cross he deserved, but in a remarkable break with tradition he is to be honoured by the Navy by having a new submarine named after him. The HMAS Sheean will be launched in the year 2000. No Ordinary Seaman has ever been remembered in such a way before.

Teddy Sheean was never awarded the Victoria Cross he deserved, but in a remarkable break with tradition he is to be honoured by the Navy by having a new submarine named after him. The HMAS Sheean will be launched in the year 2000. No Ordinary Seaman has ever been remembered in such a way before.© David Lowe, 1998

Please contact David's agent, Belinda Maxwell, at ICS and Associates, Sydney Australia, for more information.